The anatomic boundaries of the perineum are the pubis, thighs, and buttocks and can be divided into an anterior urogenital and a posterior anal triangle by drawing a line between the ischial tuberosities (Fig. 3) (7).

The perineal body is a tendinous structure in the midline of the perineum between the anus and the vaginal introitus, which provides a central point of fixation for the superficial transverse perineal muscle, the striated urogenital sphincter (formerly the deep transverse perineal muscle), the bulbocavernosus muscles anteriorly, and the external anal sphincter posteriorly (3). The perineal membrane, formerly the urogenital diaphragm, refers principally to the deep transverse perineal muscles and associated superior and inferior fascia.

This fibromuscular sheet is triangular shaped, with openings for the urethra and vagina, and supports the anterior triangle. Voluntary contraction of the perineal membrane results in vaginal compression and provides stability to the perineum during periods of increased intrabdominal pressure.

The clitoris is located at the apex of the urogenital triangle and is composed of a glans, shaft, and crura. The shaft is anchored to the pubic bone by the suspensory ligament. The crura run posterolaterally along the pubic rami. The urogenital triangle is bordered laterally by the ischiocavernosus muscles, which originate from the ischial tuberosities and the free posterior crura and insert onto the anterior crura and the body of the clitoris (3). The bulbocavernosus muscles run on each side of the vaginal vestibule beneath the labia majora from the pubis to the perineal body.

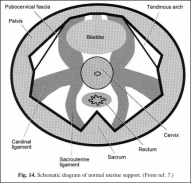

Fig. 14. Schematic diagram of normal uterine support. (From ref. 7.)

Beneath the bulbocavernosus muscles are the vestibular bulbs, which are highly vascular erectile tissue. The Bartholin gland is found at the inferior aspect of the bulb; therefore, care should be taken to minimize bleeding when dissecting in this area (3).

Of clinical significance, a fibrous fat pad lies just beneath the skin of the labia majora, which can be used as a vascularized flap (Martius flap) when a multilayer vaginal closure is necessary.

Fig. 15. Schematic diagram of normal vaginal support. (From ref. 7.)

The strength of the graft is derived from termination of the round ligament into the fibrofatty tissue. The flap can be based inferiorly off the inferior labial artery, a branch of the internal pudendal, or superiorly off the superficial external pudendal artery (10).

The posterior triangle is described briefly as it relates to posterior vaginal wall prolapse.

{pagebreak}

Fig. 16. Schematic diagram of the rectovaginal septum. (From ref. 11.)

The anatomy and function of the anal continence mechanism is complex and is outside the scope of this text; however, defecatory, voiding, and sexual issues are all interrelated and should be addressed during evaluation. The apex of the posterior or anal triangle is the coccyx. The anus is located in the midline. An important space within the posterior triangle is the posterior aspect of the ischiorectal fossa through which the pudendal vessels and nerves traverse. This fossa is bordered by the LAG superomedially, the obturator internus anterolaterally, and the skin inferiorly (3).

The rectovaginal septum is an extension of the peritoneal cul-de-sac between the posterior vagina and the rectum to the perineal body, separating the urogenital and rectal compartments (Fig. 16) (11). The septum is comprised of two distinct layers: the vaginal

Fig. 17. Schematic diagram of various breaks in the rectovaginal septum seen in patients with rectoceles. (From ref. 11.)

wall fascia and the prerectal fascia. It is only distally, at the perineal body, that they fuse.

Proximally, the septum merges with the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex, providing support for the posterior vaginal apex. Laterally, this fascial layer attaches to the ischiococcygeus and pubococcygeus just below the ATFP (11). Furthermore, the pubo-coccygeus muscle provides support for the proximal posterior vagina and intrapelvic rectum. Transverse detachment of the rectovaginal septum from the perineal body may result in a distal rectocele, or disruption of the prerectal fascia may result in a more proximal rectocele (Fig. 17).

CONCLUSION

Each year in America an estimated 400,000 women undergo surgery for pelvic floor dysfunction. Nearly 30% of the surgeries performed are reoperations (12). Clinicians must have a clear understanding of functional anatomy and pathophysiology to accurately diagnose and effectively treat disorders of the female pelvis. Successful pelvic floor reconstruction requires consideration of the primary concern and any other often-associated pelvic floor disorders.

—-

Melissa Fischer, MD, Priya Padmanabhan, MD, and Nirit Rosenblum, MD

—-

{embed=“ref/1”}